Huon pine specimen in the Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens. Image Reference

What’s in a name?

Lagarostrobos franklinii

From the Greek words for narrow (lagaros) and cone (strobilos), and franklinii commemorating Sir John Franklin, an early Arctic explorer who was also the Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) from 1837-1843.

The vernacular name of ‘Huon pine’ derives from the Huon River south of Hobart, where the living tree was first found. The river was named in honor of commanding officer Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec of the French Bruni d’Entrecasteaux who first explored this region during their expedition of 1792.

From an Age of Dinosaurs

An Incredible Record of the Past

The Huon pine ancestry can be traced back in time with Palynology, the study of fossilised plant pollen records. These preserved records have provided evidence that shows the genus Lagarostrobos has been around for at least 100 million years and potentially more. Around 100 million years ago the Australian continent was much further south, in the southern polar zone of the world, with this area being a much warmer place than it is today. It had not yet fully split from what was left of the super-continent known as eastern Gondwana. At that stage it was still a conglomeration of landmasses that eventually would become Antarctica, Australia, New Zealand and New Guinea.

This was a time very different to ours, where Australia was wetter and warmer with dinosaurs dominating the land, seas and skies. During this period Lagarostrobus and other primitive conifers were dominant in many areas of Australia including what is now Victoria and South Australia. Ancient preserved pollen records from Victoria have shown that Lagarostrobos existed there up until the very recent geological past, around 150,000 years ago.

Watching Your Nails Grow

Around 70 million years ago the Australian continent was still much further south than its present location and still attached via a land bridge to what would become Antarctica. Due to

continental drift it eventually split from Antarctica around 45 million years ago gradually moving in a northerly direction at roughly the speed it takes for your fingernails to grow.

As it moved north its land mass gradually dried out, therefore confining the moisture loving relic plants like the Huon pine to increasingly isolated habitat refuges, in this case specifically the southern and western regions of Tasmania.

Curiouser and Curiouser!

Not a “Pine”!

The Huon pine belongs to a primitive plant family the Podocarpaceae, which contains some of the oldest lineages of plants on the planet; back as far as 200 million years ago.

Often called a “pine”, it is strictly not a pine tree as they do not belong to the pine family Pinaceae. They are however part of the same broader group of non-flowering, cone bearing plants known as gymnosperms that include everything from pines and cypress through to cycads and maidenhair trees.

I Love Wet Feet

Huon pines grow naturally along rivers (Riparian or Riverine), in areas of high rainfall and in ground that is subject to high moisture and periodic flooding. They cope with varying degrees of shade and sunlight and are surprisingly tolerant of a range of locations as long as they have adequate fresh water at all times. They do not tolerate drying out.

The Right Sex

Huon pines are mostly separate male or female plants. The female cones are small, soft, up to 10mm in length and are made up of fleshy seed scales that turn pinkish red when ripe. The male cones are of a similar size but turn a light tan colour when mature, releasing clouds of fine pollen when disturbed by wind or animals. Huon pines primarily rely on wind for pollination. View video of male cones releasing pollen.

Huon Pine female cones. Image Reference

A Distinctly Unique Plant

One of the world’s oldest living organisms

In the cool temperate rainforests of Tasmania individual specimens can live to more than 3000 years old, reaching sizes of up to 40 metres in height with trunk diameters in excess of 2.5 metres. One such tree discovered in the southwest in the early 1980’s was dubbed by the discoverers, including well known forest ecologist Mike Peterson, as BHP or Big Huon Pine. In the book “The Huon Pine Story” Mike describes the finding of the tree: “After traversing another two or three hundred metres I saw what I thought was a small limestone cliff, but as I got closer it suddenly became clear that it was not a cliff. It was an enormous Huon pine sitting on top of this bank with a little creek meandering beside.”

The trees often grow incredibly slowly in these cool moist locations and may take many years to thicken their trunks and increase in height. Yet in warmer areas and given the right conditions they can grow much faster. Most of the Huon pine trees that are planted in the Tasmanian rainforest garden in the Botanical Gardens have grown to these heights from young plants established around 1990.

An Ancient Being

The Mt Read Huon pine

Tasmania is home to one of the oldest organisms in the world. The Mt Read Huon pine grove from Tasmania’s western ranges is a clonal population spread over about 1 hectare, originating from a single male plant. Ancient preserved pollen from a lake near the grove shows that the trees origin dates back more than 10,500 years. The plant was discovered by forest ecologist Mike Peterson in the late 1980’s while plant collecting in sub-alpine scrub on Mt Read in Tasmania’s central west coast region. Further study on the grove took place in the early 1990’s which revealed some astonishing information about this unique specimen.

The plants are all genetically identical male clones and therefore no seeds are produced. So how did this grove establish itself as no potential seed sources exist for many tens of kilometers? One of the principle theories is that over the millennia the plant has gradually layered itself as branches weighed down by snow and ice have touched the ground and then taken root, eventually forming their own trunks. The original single trunk has long since disappeared but the plant lives on. This grove is also the highest altitude occurrence of Huon pine known. Its speed of growth is extremely slow with 25 cm cross sections taken from some trunks showing more than 1000 growth rings, that’s averaging around 4 rings per millimetre of trunk growth.

A specimen of the original Mt Read Huon pine is established in the Tasmanian plant collection at the Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens. It was originally grown from a wild collected cutting off the original plant. On visiting the plant in the garden you will notice that it is also slightly different, being a little darker green and also having thicker branchlets to the other forms of Huon pines surrounding it in the garden.

Climate records; a window into the past

Almost all of the Huon pine has a distinctive smell when brushed or bruised. This comes from the abundance of the chemical compound methyl eugenol which is present within the pine oil itself. Other plants including many common herbs and spices have varying degrees of this compound. This compound preserves the timber, preventing it from rotting for hundreds and sometimes thousands of years. The oil itself was heat extracted from the timber and sold off for its use for medical (anti-fungal) purposes and for use with various agricultural and industrial practices for some years.

Scientific studies sampling ancient buried trunks of Huon pine in the southwest of Tasmania during the early 1980’s found that some logs are virtual sub-fossils with carbon dates of up to 35,000 years. There is some evidence to suggest that some of these logs may even have much older ages, in some cases of more than 100,000 years and that the Huon pines abundant oil and the wet, airless soils have preserved these logs for extraordinary periods of time. Cross dating of tree rings from these various ancient sub-fossil logs have the potential to assist climate scientists in understanding and interpreting the Tasmanian climate over incredible time spans.

History of Human Interaction

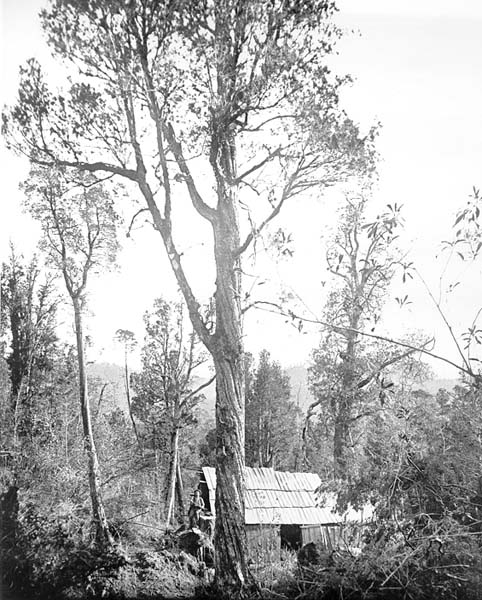

View of a piner’s camp, situated in Pine Forest, J.W. Beattie / PH30-1-1905 / NS869-1-322 Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office

The Piners

The value of Huon pine wood was quickly recognised by the first European settlers, and commercial harvesting of the timber began in the early 1800’s. Lieutenant Governor Sorell established a penal colony at Macquarie harbour on Tasmania’s west coast with the convicts harvesting the abundant Huon pine in and around the harbour, eventually processing the timber for export overseas.

Private operators had also started significant harvesting of the timber on various rivers around Tasmania’s southern and western coastlines. The piners as they were known were rugged bushmen that would often live for years in the wilderness working throughout the year harvesting timbers along river courses. A number would only return from the depths of the forests for a few weeks each year. Their dangerous occupation would be carried out with small flat bottomed boats on fast flowing and very cold rivers, in all kinds of weather. The river was their highway and a route to float out their log cargo during high water flows; in the process a number lost their lives for the harvest.

Superior value of this Wood

The oil compound methyl eugenol acts as a preservative for the Huon pine timber, preventing it from rotting rapidly. It also acts as a deterrent for many timber pests such as the damaging marine worms that previously limited the life of many an early day wooden hulled vessel. Its long life, high buoyancy on water and relative light weight made it highly regarded boat building timber by the early Europeans. In particular it was a favoured timber for small vessels such as whaling boats. However a number of large vessels were also constructed of its timber some of which still exist today.

The wood with its beautiful light honey brown colour and its easily worked qualities made it a highly prized resource for fine furniture and home finishing. The gnarled birds-eye forms of the timber are some of the most highly sought after types. In retrospect however it seems that in the early days the wood was squandered on many of the periods utilitarian needs, and what today might be regarded as wasteful uses such as roadside signage, picket fences, coffins, head boards on graves, railway sleepers, bridges and even pattern making in foundries. It was however a major export throughout the known world and soon had an established name within society as quality timber.

It is an even more highly prized timber today and its finite stock still in storage means that it will only continue as a rare and much sought after commodity. Most timber today is from stock piles and from underwater salvaging sources. Logs that have lain underwater in some cases for centuries, have been recovered with the wood still in a perfect condition. This wood is then still available to supply the trades of the specialist craftsman, artists and wood working enthusiasts.

Conservation

Today around 85% of the remaining wild populations of Huon pine are within reserves across the state. The Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens plays an incredibly important role in the conservation of the Huon pine and many other rare and threatened species of Tasmanian plants through the Gardens Tasmanian Seed Conservation Centre TSCC.

In 2016 staff from the TSCC collected an estimated 92,000 seeds from 32 trees at Corinna in North West Tasmania, for preservation in the Tasmanian seedbank. An equal collection will also be sent to England for the Millennium seedbank based in Wakehurst, that is managed by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. This is a key project to ensure the preservation of the worlds genetic heritage for all future generations.